The Money Mind: Ray Dalio and the Art of the Economic Machine

How a public failure taught the world's biggest hedge fund manager to treat the economy like a machine—and how you can steal his operating system.

The Man Who Saw the Avalanche

On a crisp autumn day in 2008, the global financial system was suffering a cardiac arrest. Lehman Brothers had dissolved into dust. The S&P 500 was in a freefall that would eventually wipe out $11 trillion in household wealth. On the trading floors of New York and London, panic wasn’t just an emotion; it was the operating system. Men and women who had spent decades building fortunes watched them evaporate in hours.

But in the woods of Westport, Connecticut, inside the fortress-like headquarters of Bridgewater Associates, the mood was eerily calm.

Ray Dalio, the founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, wasn’t panicking. He wasn’t even surprised. For two years, his computers had been flashing red. While the rest of the world was dancing to the tune of a housing boom, Dalio’s “Depression Gauge” (a proprietary system tracking debt levels relative to income) had signaled that the music had stopped long ago.

Dalio didn’t just move his clients’ money to safety; he positioned them to profit from the destruction.

That year, while the average hedge fund lost 19% and the stock market lost 37%, Dalio’s flagship Pure Alpha fund returned 14%. It wasn’t luck. It was the result of a worldview that treats the global economy not as a chaotic beast, but as a simple, mechanical machine.

But to understand how Dalio built this machine, we have to go back to the day he broke it.

The Billion-Dollar Humbling

If you met Ray Dalio in 1981, you might not have liked him. He was brilliant, yes, but he was also brash, loud, and supremely confident. He had founded Bridgewater out of his two-bedroom apartment in 1975, and by the early 80s, he felt invincible.

In 1982, Dalio made a call. He looked at the massive debts held by Latin American countries and calculated that they couldn’t possibly pay them back. He predicted a massive default that would shatter the US banking system and trigger a depression worse than the 1930s.

He was so sure of this that he bet everything on it. He went on Wall Street Week, a popular TV show, and told the world a crash was coming. He testified before Congress with the swagger of a man who knew the future.

And then, the default happened. Mexico defaulted in August 1982. Dalio looked like a genius.

For about a week.

What Dalio hadn’t accounted for was the Federal Reserve. The Fed, led by Paul Volcker, responded to the crisis by printing money and stimulating the economy. Instead of crashing, the stock market began one of the greatest bull runs in history.

Dalio was on the wrong side of the trade. The market ripped upward, and Bridgewater was crushed.

The result was total ruin. Dalio didn’t just lose his clients’ money; he lost his company. He had to fire every single employee. His friends. His colleagues. He was left alone in the office. It got so bad that he had to borrow $4,000 from his father just to pay his family’s grocery bills and keep two cars in the driveway.

“I was so arrogant that I was dead wrong... It was the most painful experience of my life, but it turned out to be the best.” — Ray Dalio

This was the crucible. Most investors would have quit or blamed the market. Dalio did something rarer: he blamed his own brain. He realized that his “gut feeling” was a liability. He needed a way to move from “I’m right” to “How do I know I’m right?”

He rebuilt Bridgewater from scratch, but this time, he replaced ego with Radical Truth.

The Superpower: Viewing the Economy as a Machine

Dalio’s intellectual edge comes from a simple realization: The economy is not mysterious. It is just the sum of millions of simple transactions repeated over and over again.

Most investors focus on the noise (earnings reports, political scandals, CEO tweets). Dalio ignores the noise and focuses on the gears.

The Three Big Forces

Dalio teaches that all economic activity is driven by three main forces:

Productivity Growth: People slowly getting better at making things over time. This is a straight line up.

The Short-Term Debt Cycle: This lasts 5–8 years. It’s what we call “Recessions” and “Booms.” Central banks control this by raising and lowering interest rates.

The Long-Term Debt Cycle: This lasts 75–100 years. This is the dangerous one. It happens when debt becomes so high that interest rates can’t act as a lever anymore (because they are already at zero). This leads to massive deleveraging (like the Great Depression or 2008).

Most investors only see the Short-Term cycle. Dalio’s superpower is seeing the Long-Term cycle. He studies history—the Roman Empire, the Dutch Republic, the British Empire—to see how these cycles repeat. His philosophy is: “Everything has happened before, and it will happen again.”

Navigating these debt cycles requires more than just macro awareness; it requires the rigorous, math-based position sizing championed by Edward O. Thorp in his approach to beating the market.

The Strategy: The Search for the Holy Grail

After his 1982 failure, Dalio became obsessed with safety. How could he make money without the risk of being wiped out?

He found the answer in a mathematical concept he calls “The Holy Grail.”

The math is simple but profound: If you own one stock, you have a high risk (volatility). If you add a second stock that moves exactly like the first one (correlated), you haven’t reduced your risk at all.

But, if you find 15 return streams that are uncorrelated—meaning they have nothing to do with each other (e.g., Gold, British Bonds, Japanese Tech Stocks, US Real Estate)—you can reduce your risk by 80% without reducing your expected profit.

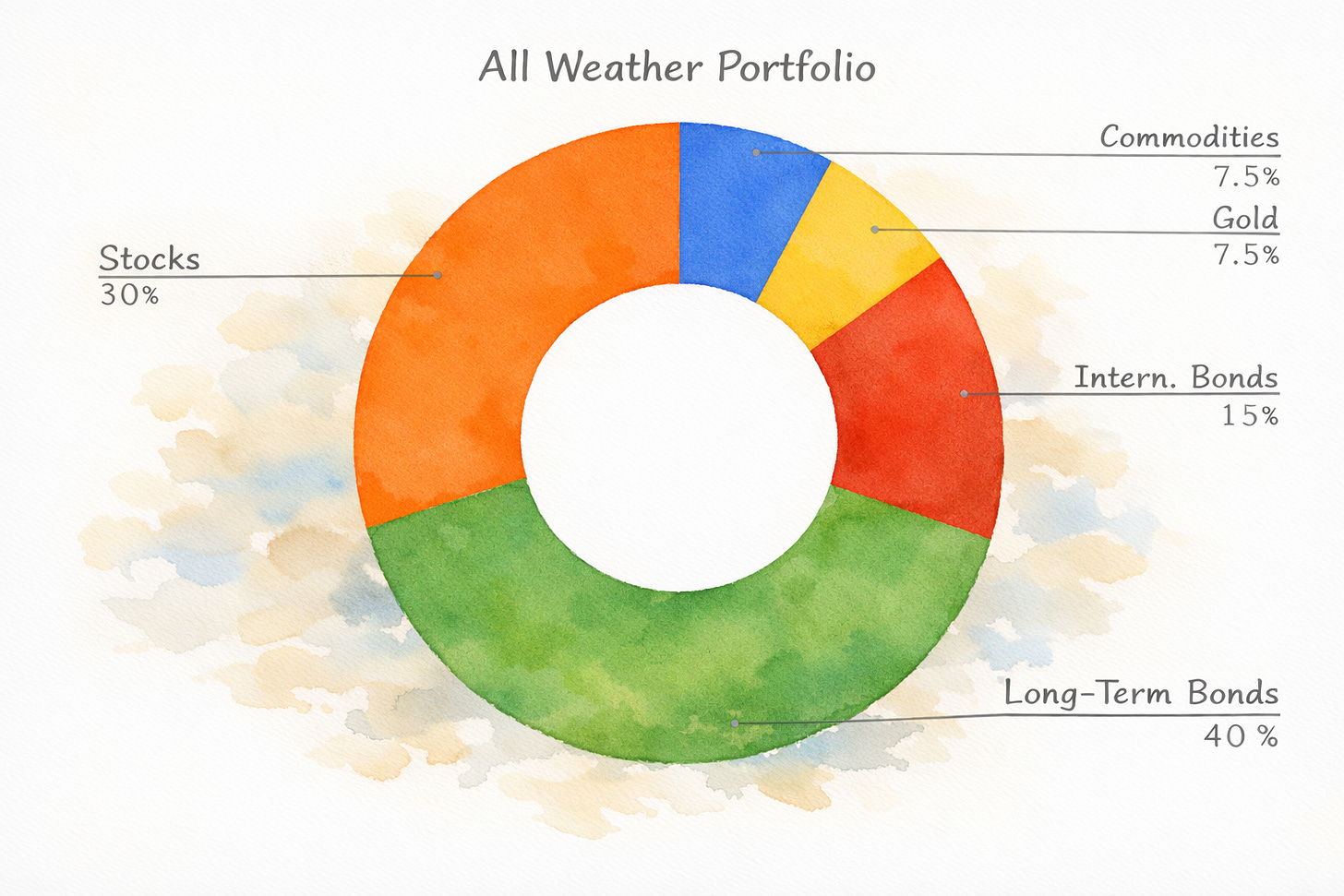

The “All Weather” Revolution

This led to his most famous invention: Risk Parity.

Traditional advice says to hold a “60/40” portfolio (60% Stocks, 40% Bonds). Dalio argues this is a trap. Why? Because stocks are three times more volatile than bonds. In a 60/40 portfolio, 90% of your risk is actually coming from the stocks. If stocks crash, you crash.

Dalio’s “All Weather” approach balances the risk, not the dollar amount. He leverages up the boring stuff (bonds) so they have the same impact as the exciting stuff (stocks). This creates a portfolio that is indifferent to which way the economic wind blows.

Inflation rising? Gold and Commodities go up.

Deflation hitting? Long-term bonds soar.

Growth booming? Stocks rally.

He built a boat that doesn’t care which way the waves are moving.

The Culture: Radical Transparency (Or, The Cult of Logic)

You cannot talk about Dalio without talking about the culture of Bridgewater. It is famously… unique.

Dalio runs his firm like an intellectual Navy SEAL team. The core principle is Radical Transparency.

Tape Everything: Every meeting is recorded. If you talk about someone behind their back, you will be fired. You must say it to their face.

The Dot Collector: In meetings, employees use iPads to rate each other in real-time on attributes like “Logic,” “Creativity,” and “Composure.” A 24-year-old junior analyst can (and is expected to) tell Ray Dalio that his idea is “illogical” if the data supports it.

Believability Weighting: Not all opinions are equal. In a democracy, everyone gets one vote. At Bridgewater, your vote is weighted by your track record in that specific subject.

To outsiders, it looks like a cult. To Dalio, it’s an “Idea Meritocracy.” It eliminates the greatest enemy of good investing: the human ego.

Steal Their Brain: Applying Dalio to Your Life

You don’t have access to Bridgewater’s supercomputers or their 1,500 employees. But you can steal the operating system.

1. The “Pain Button” Technique Dalio believes that Pain + Reflection = Progress. Most people try to hide their mistakes. Dalio journals them. When you make a bad investment (or a bad life decision), stop. Don’t brush it off. Write down exactly what happened. What caused the failure? What rule can you create to ensure it never happens again?

2. The “What is the Mechanism?” Question When you see a headline like “Tesla Stock Soars,” don’t just accept it. Ask: What is the mechanism? Is it because they sold more cars? Or is it because interest rates dropped, making growth stocks more attractive? Stop looking at the outcome and start looking at the cause-and-effect linkage.

3. Diversify by “Season” Don’t just buy 10 tech stocks and call it “diversified.” Look at your portfolio.

Do you have something that wins if inflation destroys the dollar? (Gold/Commodities/Bitcoin)

Do you have something that wins if the economy collapses? (Long-term Treasuries)

Do you have something that wins if the economy booms? (Stocks)

If you only have stocks, you are betting on a perpetual summer. Winter always comes eventually.

The Verdict

Ray Dalio is the Philosopher King of finance. He is not a gambler; he is an engineer who views the world through the lens of history and probability.

This style is for you if:

You are analytical and prefer systems over “gut feel.”

You are terrified of losing money and want a smoother ride.

You are willing to accept lower returns in a bull market in exchange for survival in a bear market.

Avoid this style if:

You crave the dopamine hit of finding the “next big thing.”

You find the idea of owning “dead assets” like Gold or Bonds frustrating during a tech boom.

Dalio’s ultimate lesson is not about money. It is about reality. He teaches us that we cannot make the world behave the way we want it to. We can only understand how it actually works, and position ourselves to ride the waves rather than drown in them.