Why You Need To Know About The Capital Cycle Theory

How to Stop Buying High and Selling Low Like a Sucker.

Let’s be honest. Most investment theories are about as exciting as watching paint dry on a graph of historical bond yields. They are usually full of Greek letters, complex formulas, and the assumption that humans are rational beings (which, if you’ve ever seen a line for a limited-edition sneaker drop, you know is a lie).

But then there is the Capital Cycle Theory.

This isn’t just a theory; it is the “Circle of Life” for money. It is arguably the single most valuable tool for understanding why the hottest industry in the world just crashed, and why a boring company you’ve never heard of is suddenly minting millionaires.

Here is why you need to know it, how it works, and a real-world example of how one company got a “moat for free” while everyone else was watching a unicorn implode.

The Obsession with “Demand” (The Trap)

Imagine you are an investment analyst. You wake up, put on your Patagonia vest, and start looking for the “Next Big Thing.”

You look at Demand.

“Everyone is buying EVs!”

“Everyone is eating plant-based meat!”

“Everyone is using AI chatbots to write their wedding vows!”

The problem? Everyone else is looking at demand, too. Predicting demand is incredibly hard because consumers are fickle. Remember when we all thought we’d be riding Segways to work? Exactly.

The Capital Cycle Theory flips the script. It says: Ignore demand. It’s a trap. Look at Supply.

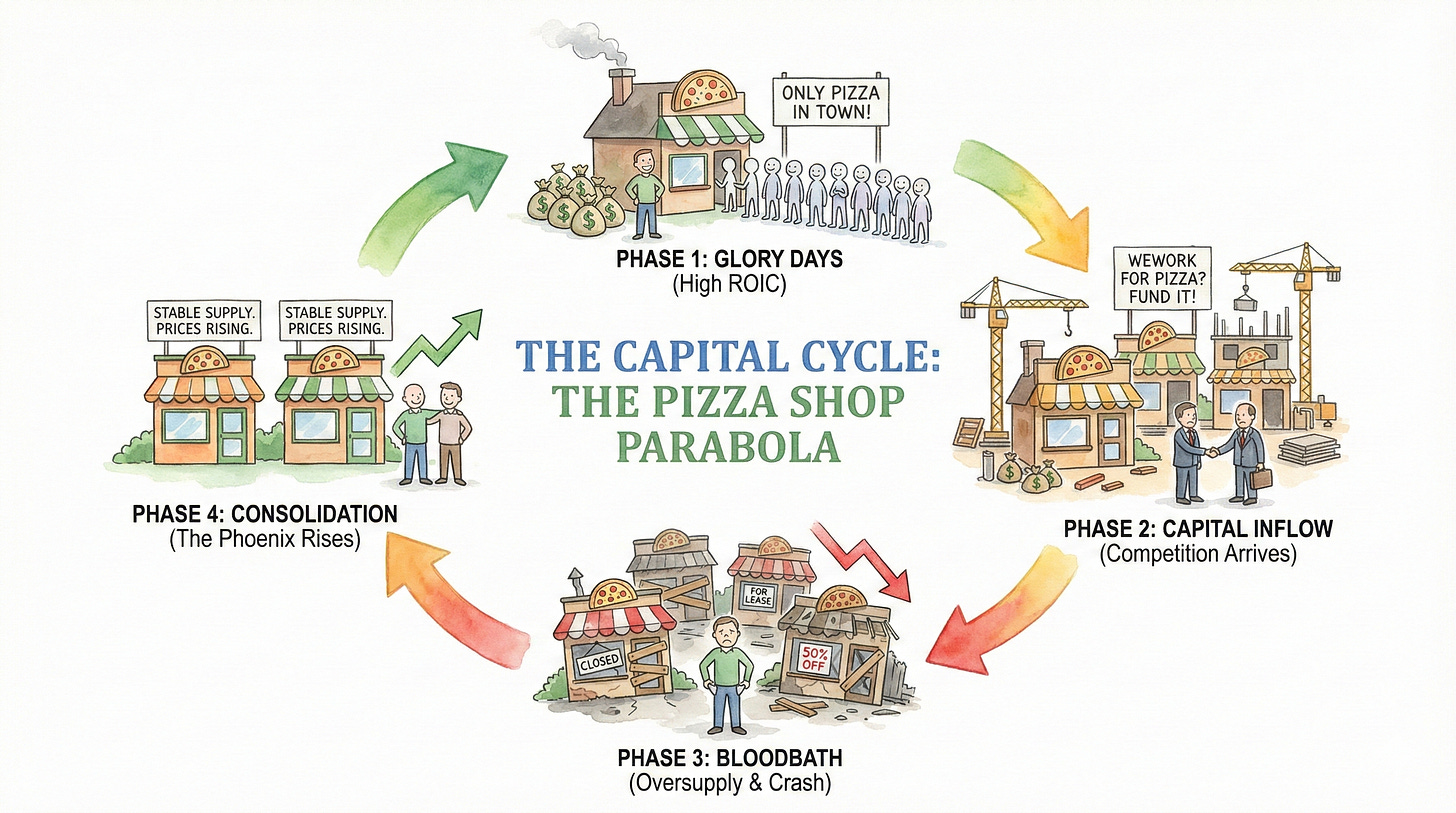

The Theory in a Nutshell: The Pizza Shop Parabola

Let’s strip away the Wall Street jargon and use a pizza shop example.

Phase 1: The Glory Days

You open the only pizza shop in town. The pizza is mediocre, but you are the only game in town. You have high pricing power. You are making a killing. Returns on Invested Capital (ROIC) are through the roof.

Phase 2: The Shark Attack (Capital Inflow)

Your neighbor, Bob, sees you driving a new Porsche. He thinks, “I can make pizza.” Then a private equity firm sees Bob making money. They think, “We can scale this.” Investment bankers (who can smell fees the way a shark smells a drop of blood in the ocean) start taking pizza chains public.

Suddenly, there are 10 pizza shops.

Phase 3: The Bloodbath (Overcapacity)

Now, there is too much supply. To sell pizza, you have to lower prices. You offer “Buy one, get two free.” Your margins get crushed. Bob goes bankrupt. The private equity firm writes off the investment.

This is where most retail investors lose their shirts because they bought in during Phase 2.

Phase 4: The Phoenix (Consolidation)

The pizza sector is now hated. No one wants to invest in it. The weak shops close down. The equipment is sold for scrap.

But here is the magic: People still eat pizza.

Eventually, only two shops remain. With no new competition entering (because investors are scared), the survivors raise prices again. Profits soar. The cycle restarts.

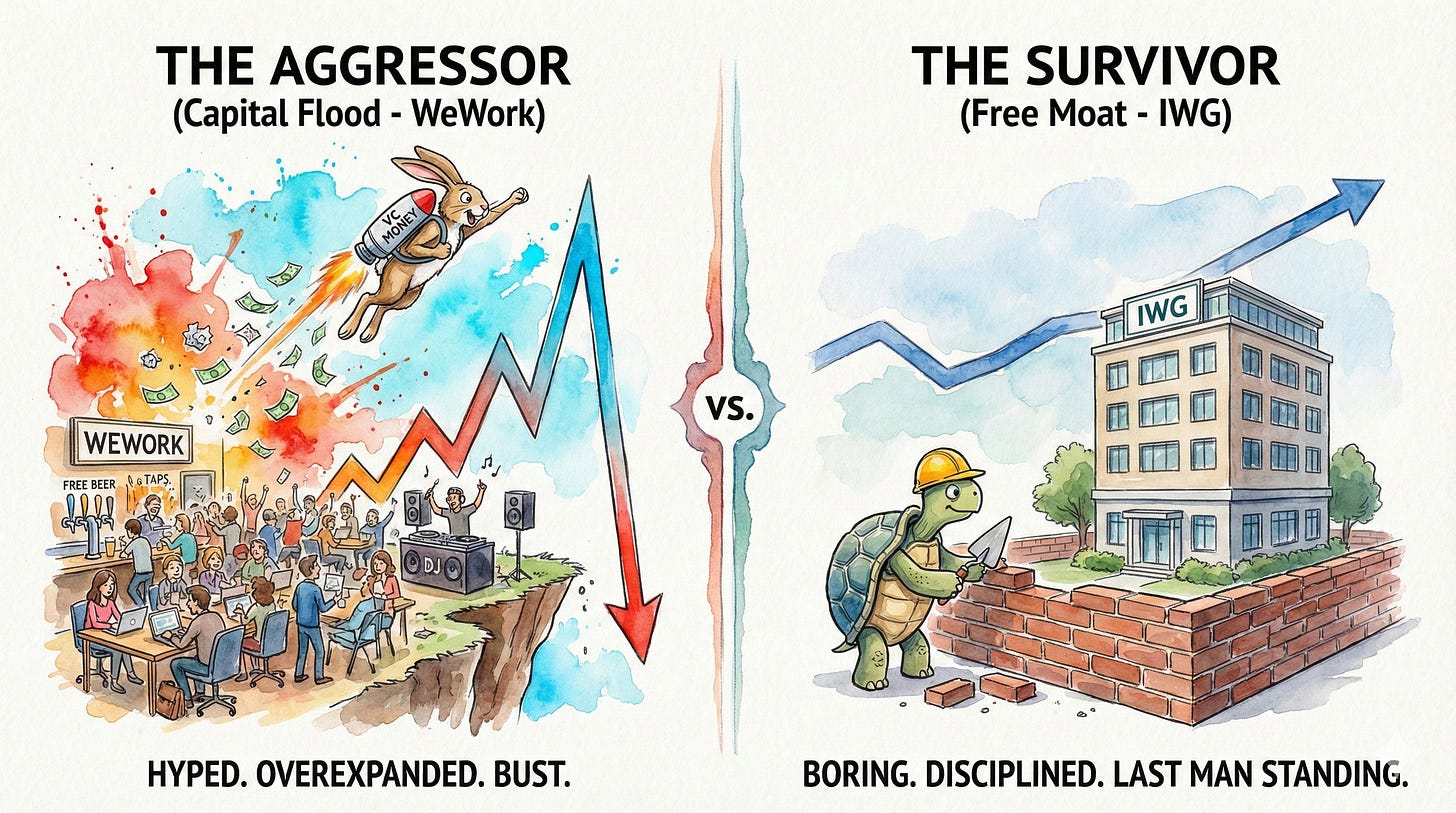

The Real World Case Study: WeWork vs. IWG

How to get a moat for free.

This isn’t just theory. We just watched it play out in real-time with WeWork and IWG (formerly Regus).

The Aggressor: WeWork (The Capital Flood)

In the late 2010s, WeWork was the “Pizza Shop Phase 2” on steroids. Fueled by SoftBank and massive hype, they raised billions of dollars. They didn’t care about profits; they cared about growth.

The Move: They leased office space everywhere, renovated it to look like a hipster coffee shop, and rented it out cheaply.

The Distortion: They flooded the market with supply. They were selling $1 bills for 80 cents.

The Victim (Initially): IWG

IWG was the boring incumbent. They had been doing flexible office space for 30 years. They were profitable, but unsexy.

The Pain: When WeWork came to town offering free beer and subsidized rent, IWG suffered. They couldn’t raise prices. Their margins got squeezed. Investors hated them because they looked like a dinosaur compared to the “tech-enabled” unicorn.

The Bust: The Great Cleansing

Then, gravity happened. WeWork’s valuation collapsed from ~$47 billion to bankruptcy/restructuring. The money tap turned off.

Supply Destruction: WeWork stopped expanding. They started closing locations and rejecting leases. The irrational supply vanished from the market.

The Winner: IWG (The “Free Moat”)

This is the Capital Cycle payoff. IWG didn’t have to spend billions to defeat their rival. Their rival defeated itself.

The Result: IWG is arguably the last major player standing with scale. With WeWork out of the way (or severely hobbled), the irrational pricing stops. IWG can now raise prices.

The Moat: IWG effectively got a competitive moat handed to them for free, simply by surviving the “Capital Hurricane” that WeWork created. Now, no investor wants to fund a new WeWork, meaning IWG faces limited competition for years.

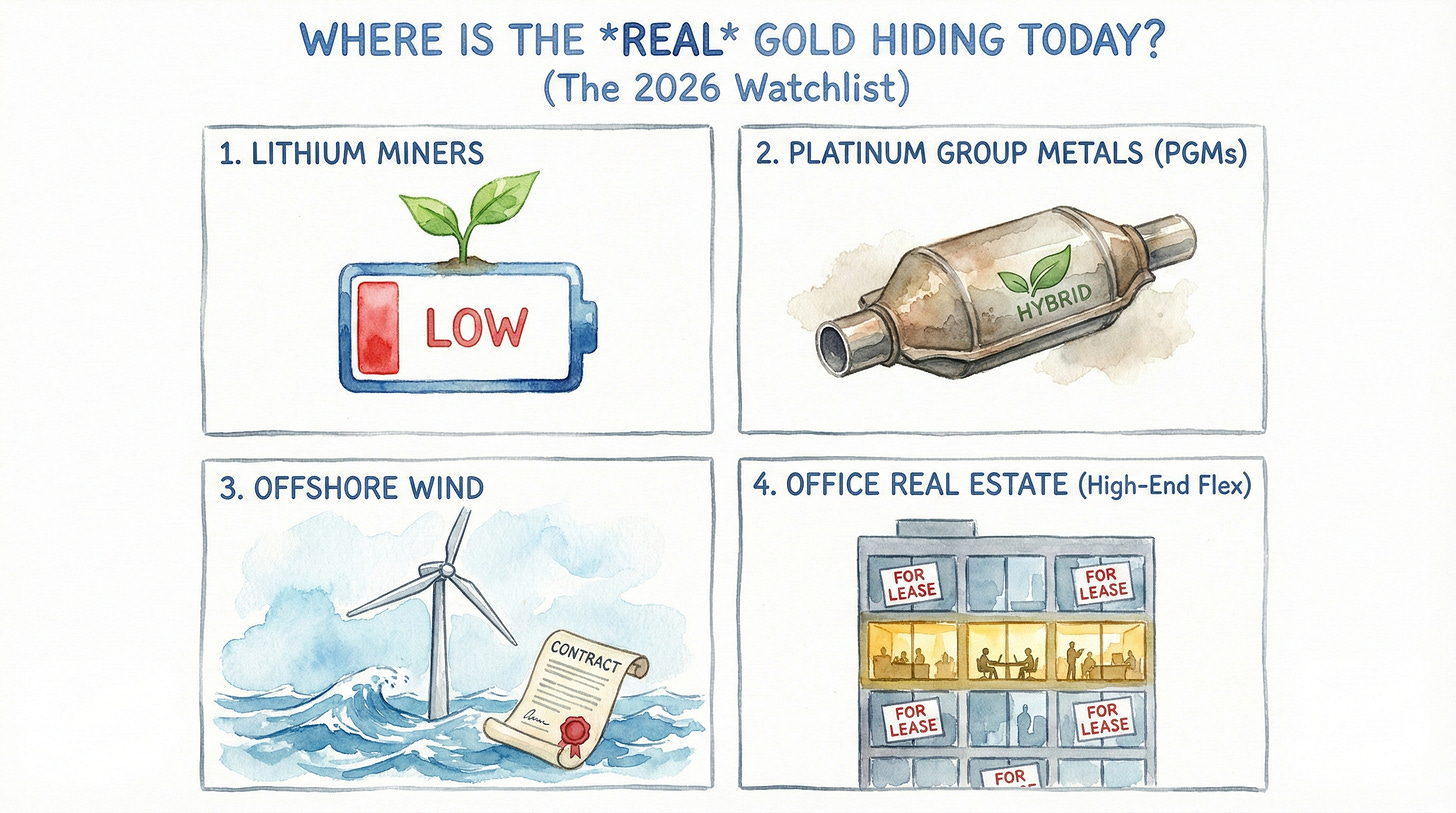

Where Is The Real Gold Hiding Today? (The 2026 Watchlist)

To find the true opportunity, we need to look at what is currently in Phase 4: hated, bankrupt, and supply-constrained.

Here are the sectors that I think fit the bill in 2026:

1. Lithium Miners (The “EV Winter” Survivors)

The Vibe: Complete despair. After the massive boom in 2022, the price of Lithium crashed 80%+ by 2025 due to oversupply and slower EV adoption.

The Reality: We still need batteries (especially for grid storage, which is booming).

The Setup: Low prices have forced mines to close in Australia and China. Projects have been cancelled. Supply has been destroyed.

The Play: The few low-cost producers (like Albemarle or SQM) who survived the crash are now looking at a market where demand is growing, but no new supply can come online for years because nobody invested in 2024/2025.

2. Platinum Group Metals (PGMs)

The Vibe: “Dead Technology.” Everyone thinks electric cars don’t need spark plugs or catalytic converters, so Platinum and Palladium are useless.

The Reality: The transition to pure EVs is slower than expected. Hybrids are winning, and hybrids do need PGMs.

The Setup: Prices have been so low that mines in South Africa (where most of the world’s supply comes from) are shutting down shafts. We are entering a massive supply deficit just as hybrid sales are hitting record highs.

3. Offshore Wind (The “Broken” Industry)

The Vibe: A disaster zone. In 2023-2025, companies like Ørsted took massive losses because inflation killed their project economics.

The Reality: Governments still have green energy targets they must hit.

The Setup: Because the industry lost so much money, they stopped bidding on new projects. Now, governments are panicking and offering much higher prices to lure them back. The companies that survived the bust are about to sign contracts at much juicier margins.

4. Office Real Estate (Specifically High-End Flex)

The Vibe: Toxic. “Work from home killed the office.”

The Reality: Most office companies are trading at deep discounts to their asset value. But as we saw with IWG, the competition has vanished.

The Setup: No bank will lend money to build a new office tower today. Construction has halted. Supply is capped for the next 5-10 years. The incumbents own the only game in town.

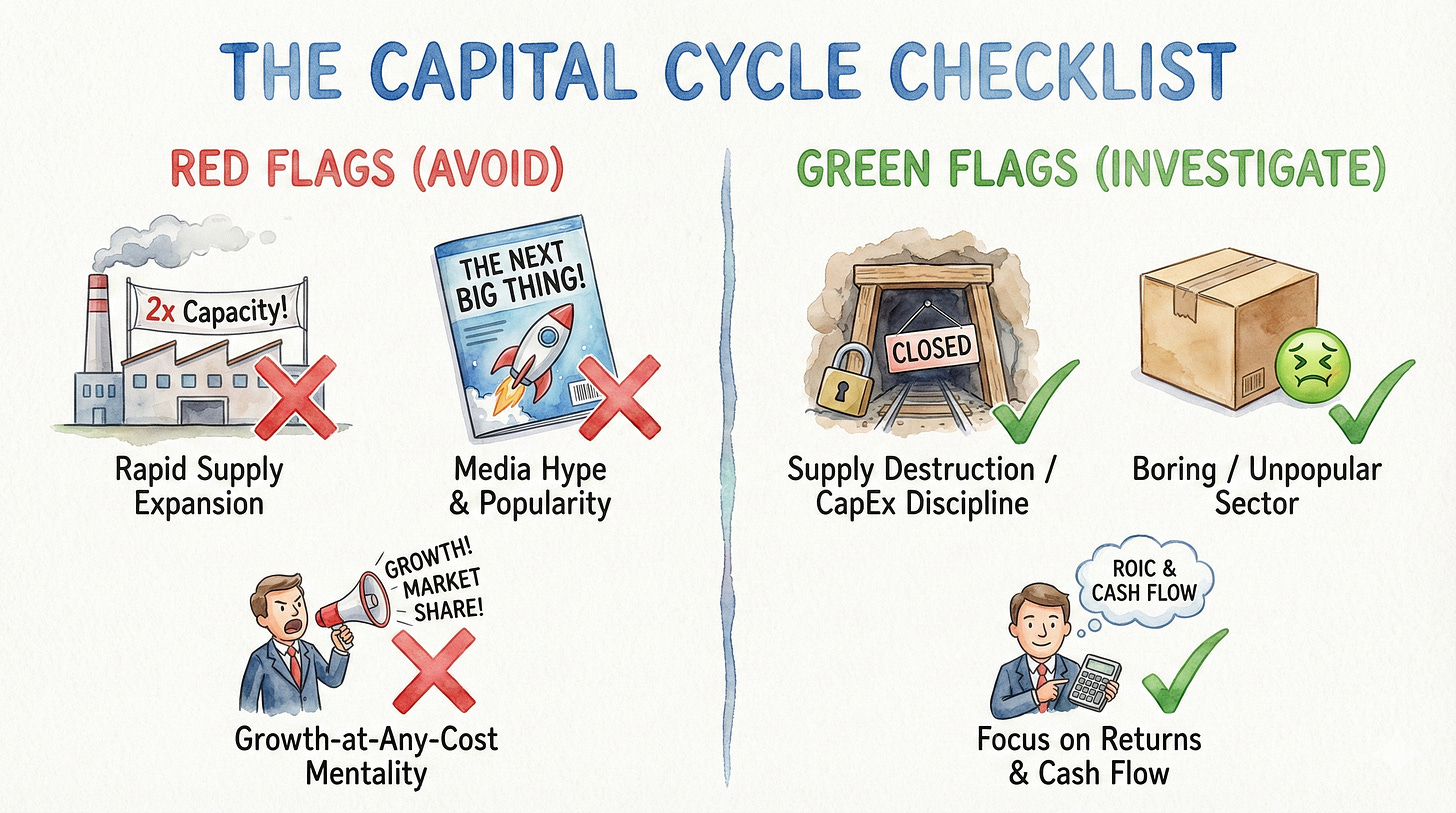

How to Use This (Without Losing Your Mind)

You don’t need to be a hedge fund manager to use this. You just need to be a bit of a contrarian.

1. Watch the Capex (Capital Expenditure)

If you see an industry where every company is building new factories, launching new mines, or spending billions on new servers—be careful.

Red Flag: “We are doubling our capacity to meet future demand!”

Translation: “We are about to destroy our profit margins.”

2. Look for the “Yuck” Factor

Look for industries that magazines make fun of. Coal? Tobacco? Shipping? Old-school manufacturing? If capital is leaving an industry (no IPOs, no new startups), but the product is still necessary, you might have found a goldmine.

3. Beware the “Growth at Any Cost” CEO

If a CEO talks about “market share” more than “Return on Invested Capital,” run away. They are the ones who will overexpand the pizza shop (or the coworking space).

The Takeaway

The Capital Cycle Theory teaches us that high returns attract capital, and capital kills returns.

Investing is counter-intuitive. It feels good to buy what is popular. It feels safe to follow the crowd. But the crowd is usually busy creating the next bubble.

So, next time you see a magazine cover declaring a certain industry “The Future of Everything,” remember WeWork. And maybe go look for a company that makes something boring, where the competition has already gone bust.

loved having the actual example of WeWork vs. IWG as part of the case