The Money Mind: Shelby Cullom Davis and the $900 Million Double Play

How a 38-year-old diplomat turned his wife’s $50,000 savings into a dynasty by ignoring Wall Street and buying the most boring stocks on earth.

The Greatest Track Record You’ve Never Heard Of

If you had invested $10,000 in the S&P 500 in 1947 and went into a coma for 45 years, you would have woken up rich. The market compounded at a respectable rate, and you would have had a nice retirement.

But if you had given that $10,000 to Shelby Cullom Davis, you wouldn’t just be rich. You would be a tycoon. By the time he died in 1994, that $10,000 would have turned into $38 million.

Davis turned an initial stake of $50,000 into $900 million.

He didn’t do it by inventing a computer chip. He didn’t do it by finding the next Coca-Cola. He didn’t do it by trading derivatives.

He did it by investing in the single most boring industry in the global economy: Insurance.

Davis is the ultimate proof that you don’t need to be exciting to be profitable. In fact, he proved the opposite: if you can find excitement in boredom, you can outperform almost everyone. But his true genius wasn’t just picking stocks; it was identifying a mathematical anomaly in how markets price growth. He called it the “Davis Double Play,” and it remains the most powerful engine for wealth creation in the stock market today.

The Origin Story: The Diplomat Who Hated Bonds

Shelby Cullom Davis was a late bloomer. He didn’t start investing professionally until he was 38 years old.

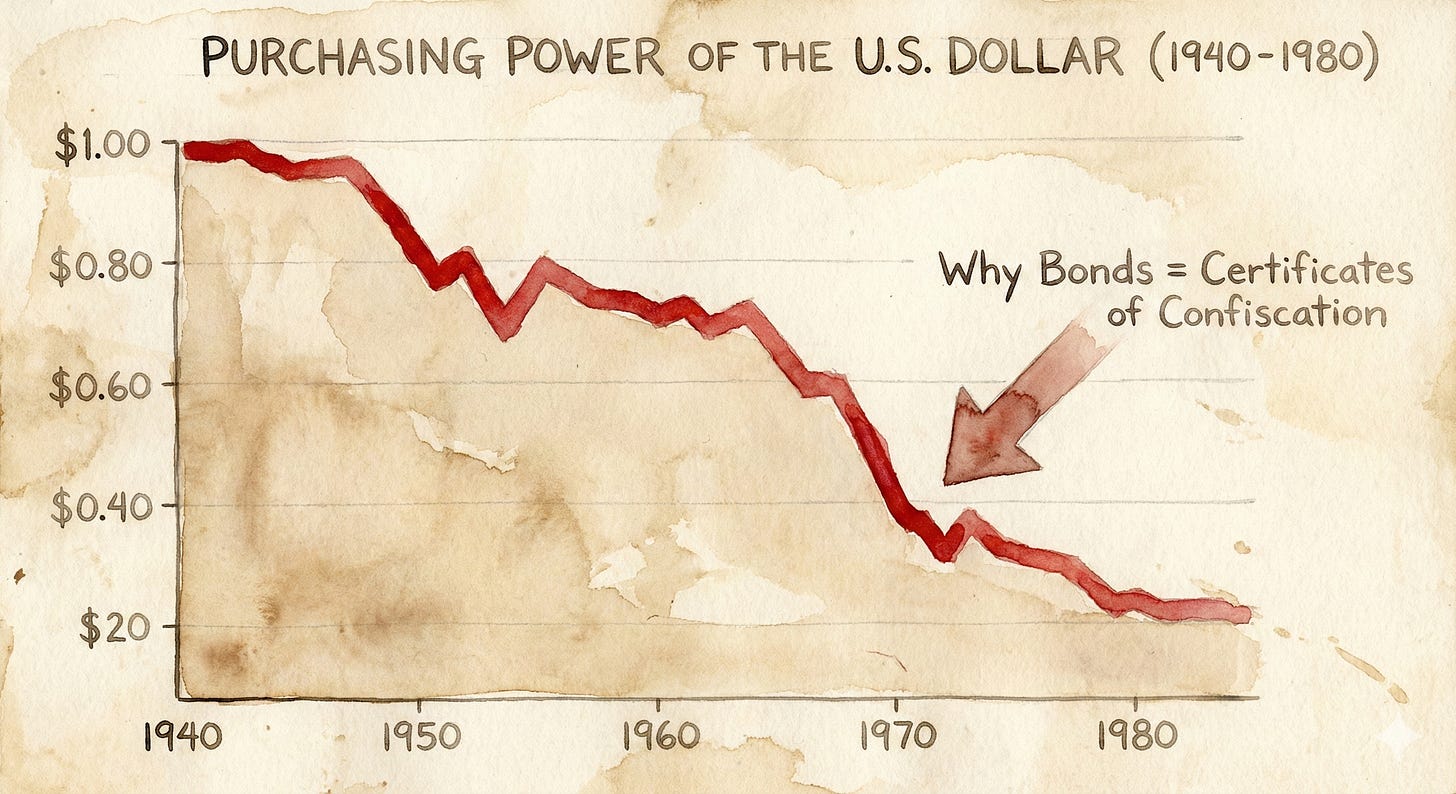

Before Wall Street, he was a scholar and a diplomat. In the 1930s and 40s, he worked in Geneva and New York, holding a front-row seat to the geopolitical chaos of the 20th century. He watched the Great Depression ravage economies. He watched World War II destroy currencies.

This experience gave him a specific, lifelong trauma: A terror of inflation.

In 1947, he quit his job to start his own firm. But he didn’t go in blind. He had spent years working as New York’s Deputy Superintendent of Insurance.

It sounds like a boring paper-pushing job, but it gave him an unfair advantage. While Wall Street ignored insurance companies as “dull,” Davis spent his days reading their regulatory filings. He discovered that insurers were hiding massive profits to avoid regulation. He knew the secrets—specifically the power of the “float” (investing customer premiums before claims are paid)—before the market did.

He took $50,000 of his wife’s money and went all in.

Did you know?

His wife, Kathryn Wasserman Davis, was an American investor, painter, philanthropist, and political activist - that lived to be 106!

The Superpower: The Davis Double Play

Why insurance?

Because insurance companies are legal money-printing machines. They collect premiums upfront, hold the money (the “float”), invest it, and pay claims years later. If inflation goes up, they simply raise the price of premiums. They are inflation-proof.

But buying good companies wasn’t enough. Davis wanted exponential returns.

This led to his discovery of “The Davis Double Play.”

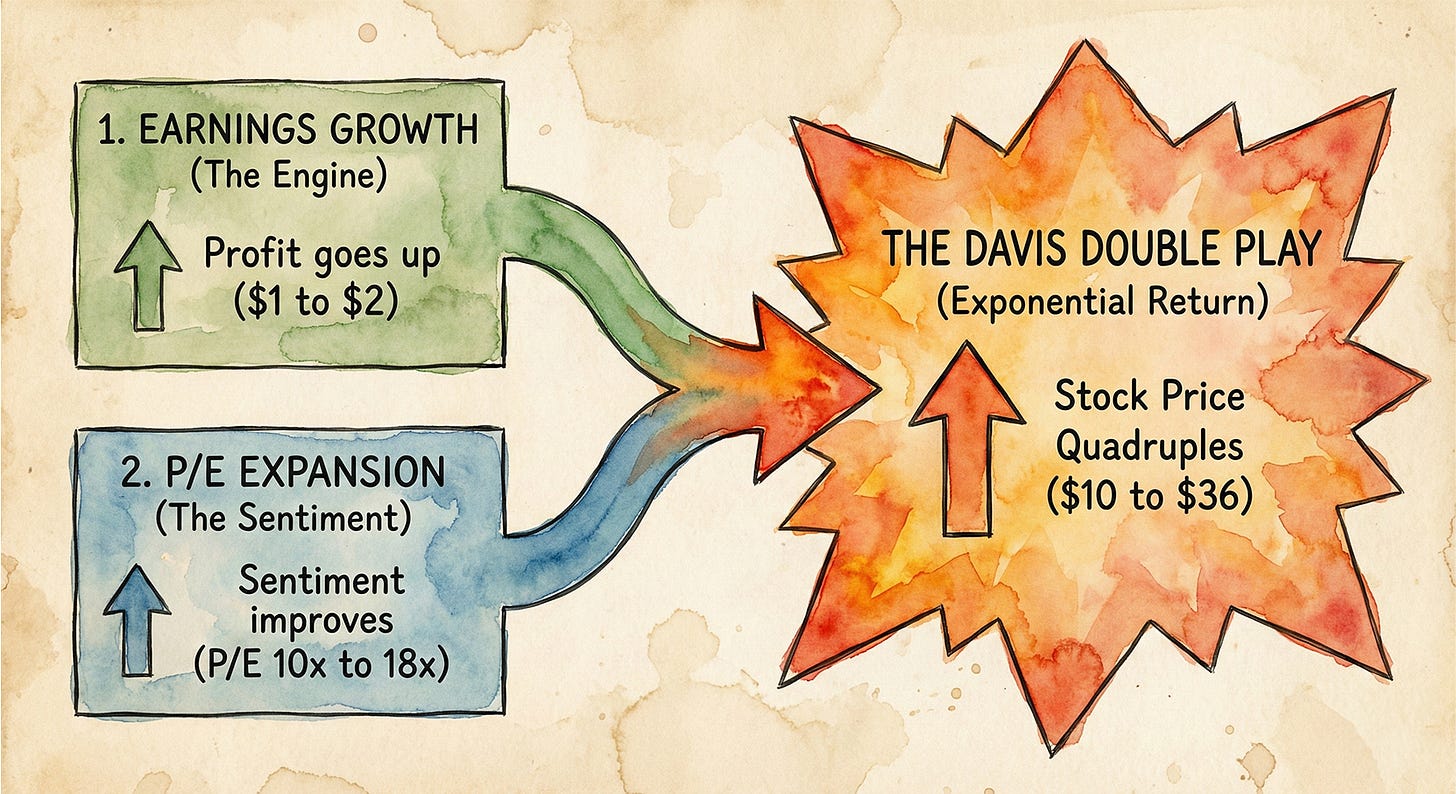

Most investors look for earnings growth. Davis realized that was only half the equation. Stock prices are calculated by:

Price =Earnings ×Valuation (P/E Ratio)

If a company grows its earnings, the stock goes up. That’s a “Single Play.” But if a company grows its earnings AND the market gets more excited about the stock (expanding the P/E ratio), the stock explodes. That’s the “Double Play.”

The Math of the Double Play: Imagine you buy a boring insurance company called “SafeCo.”

Earnings: $1.00 per share.

Sentiment: Nobody likes it. It trades at a P/E of 10.

Stock Price: $10.00.

Five years pass. SafeCo is managed well. Earnings double to $2.00.

Scenario A (The Single Play): The market still thinks it’s boring. P/E stays at 10.

New Price: $2.00 x 10 = $20.00. (You doubled your money).

Scenario B (The Davis Double Play): Because earnings are growing, Wall Street suddenly notices. They start calling SafeCo a “growth stock.” They get excited. They are now willing to pay an 18x multiple for it.

New Price: $2.00 (Earnings) x 18 (P/E) = $36.00.

The Magic: The earnings only doubled ($1 to $2), but your money nearly quadrupled ($10 to $36).

Davis dedicated his life to finding companies poised for this transformation. He didn’t buy “cheap” stocks; he bought cheap stocks that had the potential to become popular.

The Graveyard: The 1974 Crush

It sounds easy, but the Davis method required a stomach of steel. Because he was so confident in his “Double Play” theory, he did something dangerous: He used leverage.

He borrowed money to buy more stocks. In a bull market, this acts like rocket fuel. In a bear market, it is a death sentence.

In the early 1970s, the “Nifty Fifty” bubble burst. The market entered a brutal, grinding bear market. Between 1973 and 1974, the Dow Jones lost 45% of its value.

Davis’s portfolio didn’t just drop; it cratered. Because he was leveraged, his losses were magnified. He lost roughly 50% of his net worth—millions of dollars evaporated.

The pressure was immense. Banks were calling. Peers were panic-selling. The “Death of Equities” was on the cover of magazines.

But Davis didn’t sell. He looked at his insurance companies. Were they still selling policies? Yes. Were they still collecting premiums? Yes. The price had changed, but the machine was still working. He held on, white-knuckled, through the crash.

When the market turned, his leverage kicked in on the way up. The rebound made him a billionaire.

Steal Their Brain: The Davis Toolkit

You don’t need to leverage your house or buy insurance stocks to use Davis’s brain. Here is how to apply his operating system:

1. The “Silver Bullet” Question

When Davis researched a company, he didn’t just ask the CEO about their own business (they will always sell you a rosy picture). He asked a specific question: “If you had one silver bullet to shoot a competitor, which competitor would you shoot?”

Actionable Rule: This reveals who the real threat is. Don’t ask a company who they are worried about. Ask them who they would kill. Then, go research that company.

2. The “Man on the Street” Bluff

Davis didn’t trust balance sheets alone. He would call insurance brokers pretending to be a customer to see if they were pricing risks correctly.

Actionable Rule: Stop reading charts. Start testing products. If you invest in a retailer, go to the store. Is it clean? Are the staff happy? Ground-level truth beats C-suite promises.

3. “Write to Think”

Davis wrote a weekly investment bulletin for years, even when nobody read it. He said, “Putting ideas on paper forces you to think things through. You can fool yourself in your head. It’s much harder to fool yourself on paper.”

Actionable Rule: Write down your investment thesis. If you can’t articulate why you are buying a stock in one paragraph, you don’t understand it enough to buy it.

4. The 10-Year Test

Davis held stocks for decades. He hated selling because paying capital gains tax interrupted the compounding process.

Actionable Rule: Before you click “buy,” ask yourself: “If the stock market closed for 10 years, would I be happy owning this business?” If the answer is no, you are speculating, not investing.

The Human Factor: The Frugal Tycoon

Despite possessing a fortune that rivaled royalty, Shelby Cullom Davis lived like a graduate student.

This wasn’t just about hoarding pennies; it was about teaching values.

When his children begged for a swimming pool in the backyard, Davis finally agreed—on one condition: They had to dig the hole themselves. The kids spent weekends with shovels, digging until they literally hit bedrock. Only then, after seeing their sweat equity, did he pay for a bulldozer to finish the job.

The Lesson: To Davis, money wasn’t for luxury; it was fuel for the compounding machine. Spending it frivolously wasn’t just waste—it was destroying the “seeds” of future forests. He didn’t just want to save money; he wanted his children to understand the visceral effort required to earn it.

The Verdict

Shelby Cullom Davis is the patron saint of the “Boring Investor.”

Copy this style if:

You are patient (time horizon of 10+ years).

You understand that “boring” industries (insurance, waste management, infrastructure) often make the most money.

You are willing to do the qualitative work (understanding the business) to find the “Double Play.”

Run away if:

You check your portfolio every day.

You need steady income (Davis hated dividends; he wanted reinvestment).

You cannot handle seeing your portfolio drop 30-50% without selling.

I also have The Titan Test series here on Atomic Moat where I analyse companies applying the lens of famous investors. Don’t miss the Kinsale analysis I did, using the method of Shelby Cullom Davis.

Davis taught us that the market is a voting machine in the short run, but a weighing machine in the long run. And if you buy growing companies at cheap prices, the scale will eventually tip in your favor.

Really like these posts on GOATs. Thanks.

I recently read about Davis in Pulak Prasad's book - what I learned about investing from Darwin. This guy was really interesting. And I would recommend you to read that book if you haven't already. It's one of the best books on investing, ever! IMO